Trump and Birthright Citizenship

A ruling in Trump’s favor wouldn’t be the first attack on the ideals of Reconstruction. By Luke Pickrell

Next month, the Supreme Court will hear arguments over Trump’s request to roll back injunctions that block his executive order to end birthright citizenship. Since day one, Trump’s administration has challenged the Citizenship Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, which states, “All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside.”

So far, every lower court that has considered the executive order has blocked it. Currently, the Trump administration isn’t asking the Supreme Court to overturn those rulings. Instead, it wants the Justices to limit injunctions to the plaintiffs who have sued, rather than allowing the injunctions to cover everyone in the country. A ruling in Trump’s favor wouldn’t immediately end birthright citizenship, but it would weaken the authority of lower courts and pave the way for future executive action.

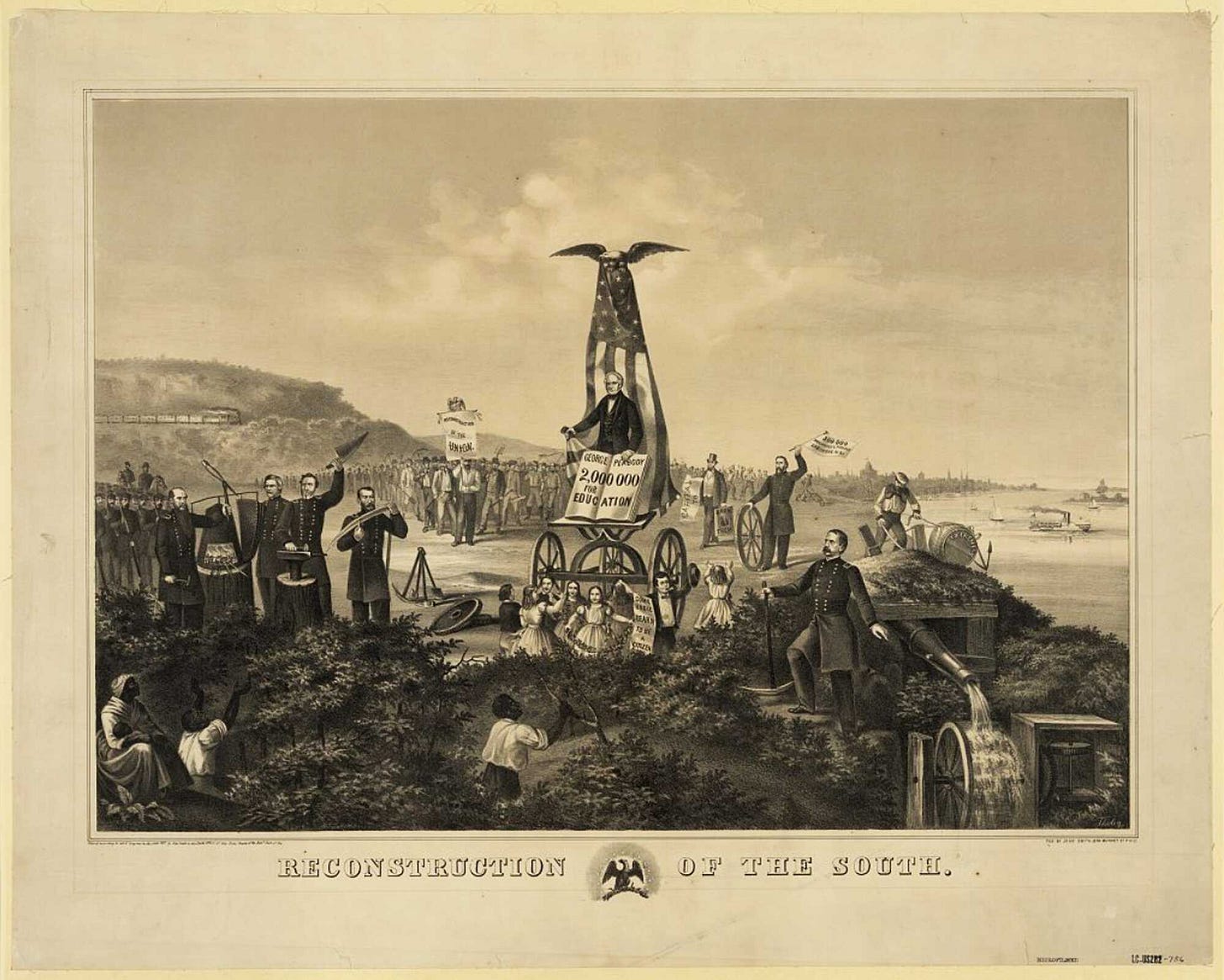

The Fourteenth Amendment is a product of the Civil War and Reconstruction, one of the most consequential struggles for democracy and universal equal rights in U.S. history. The War was fought to end slavery, an institution enshrined in the Three-Fifths Clause (Article I, Section 2) and the Fugitive Slave Clause (Article IV, Section 2), and protected by all three branches of government.

The Constitution made a violent conflict all but inevitable. As Eric Foner notes, “Since changes to the Constitution require approval by two-thirds of Congress and three-quarters of the states, an amendment abolishing slavery was clearly out of the question.” Thanks in large part to the South’s overrepresentation in the House and Senate, Americans had created — in the words of Daniel Lazare — “one of the most immovable political structures this side of the as-yet-hermetically sealed kingdoms of Korea and Japan.”

As Lucas and I discussed in a previous podcast episode, a ruling in Trump’s favor would be just the latest chapter in the Court’s long history of undermining Reconstruction. Beginning in the 1870s, the Justices used judicial review to gut the Reconstruction Amendments, interpreting them in the narrowest, most conservative ways possible. They repeatedly ruled that the federal government had no power to intervene in the states, and that the rights of citizenship barely extended to blacks.

The Thirteenth Amendment “almost immediately fell into disuse,” with the Court repeatedly ruling that Congress could not legislate against racial inequality. Instead of shielding the formerly enslaved, the Fourteenth Amendment was repurposed to protect corporations, and by the early 20th century, the Fifteenth Amendment had become meaningless in the South. “So long as disenfranchisement laws did not explicitly mention race,” explains Foner, “the justices refused to intervene even as the vast majority of the South’s African-American men lost the right to vote.”

More recently, in 2013, the Court gutted the Voting Rights Act of 1965 by eliminating its federal preclearance requirement for jurisdictions with a history of racial discrimination.

The Supreme Court “played a crucial role in the long retreat from the ideals of Reconstruction,” concludes Foner. “The process was gradual and the outcome never total, and each decision involved its own laws, facts, and legal precedents… For African-Americans, however, the practical consequences were the same. The broad conception of constitutional rights with which blacks attempted to imbue the abolition of slavery proved tragically insecure.”

Ultimately, I’m not interested in parsing the Constitution or predicting how the Justices will rule. That’s not the point. The point is to think beyond the current rules — beyond a system where a handful of unelected officials have the final say on our political and social rights. If the Court rules against Trump and upholds nationwide injunctions, the struggle for a democratic constitution continues, as always. No matter the outcome, no Supreme Court ruling changes the need for a new political foundation based on universal and equal suffrage, a unicameral legislature, and a government that reflects the people's will.