Escaping the Constitutional Bind

Luke Pickrell discusses Aziz Rana's newest book, The Constitutional Bind: How Americans Came to Idolize a Document That Fails Them

At a private gathering last year, Joe Biden warned, “If the Democrats don’t own the presidency, we’re going to find ourselves in the position where democracy is…literally at stake.” At a later event dedicated to the memory of John McCain and “the work we must do together to strengthen our democracy,” Biden explained that “history has brought us to a new time of testing” and that democracy means adherence to the Constitution and its system of separation of powers and checks and balances. During this year’s State of the Union, it took Biden all of two minutes to declare that “Not since President Lincoln and the Civil War have freedom and democracy been under assault at home as they are today.”

Americans tend to locate something called “democracy” in our ancient Constitution — as some combination of checks and balances, an impartial Supreme Court, and the phrase, “We the people” (1). The Constitution makes the U.S. special. Things go well when people respect and follow the Constitution’s rules and bad when people don’t. Biden and the Democrats are relying on this narrative to win reelection in November. Only Biden and the Democrats will respect the Constitution, maintain the division of powers between the branches of government, and, as a result, ensure nothing less than the continued orbit of the earth around the sun. Only the Constitution can stop Trump. However, this narrative is starting to fall apart. Four years ago, Daniel Lazare wrote that the Constitution was “hiding in plain sight.” Four years later, the Constitution’s hiding spot is much less secure.

With his new book, The Constitutional Bind: How Americans Came to Idolize a Document That Fails Them, Aziz Rana is doing his part, along with many others (2), to unravel our constitutional regime a little faster. The Constitutional Bind is like a leftist version of Michael Kammen’s A Machine That Would Go of Itself. Like Kammen, whose book is considered a classic in legal studies, Rana explores how non-experts have thought about and interacted with the Constitution. Like Kammen, Rana wants to take the Constitution off its imaginary pedestal and place it where it belongs: the messy world of social and political strife. Both authors aim to make the Constitution comprehensible to non-professionals and correct the myth of an uninterrupted infatuation with the Framer’s creation.

However, Kammen’s book gives the impression of being written by someone who thought the Constitution was fundamentally sound (save, perhaps, for a few elite-initiated adjustments). Rana, on the other hand, is far more skeptical. He wants to further his and the readers’ knowledge in order to change the Constitution (3). The Constitution Bind is written from the perspective of Marxists, Maoists, Civil Rights leaders, labor leaders, and other iconoclasts who struggled to understand and change America’s uniquely convoluted political system.

Resistance

Contrary to the standard narrative, Americans haven’t always held the Constitution in high regard. The first centennial celebration in 1887 was a relatively subdued affair. The Founding Fathers, whose creation was intended to maintain the Union and stabilize society, seemed far less wise after the Civil War killed two percent of the entire population (over 6 million people today). The Gilded Age was in full bloom, industrialism was spreading, and inequality was rampant. The closing of the frontier was the cherry on top, and many wondered how the United States could survive.

Rana explains that criticism of the Constitution was at its highest in the lead-up to World War One, as evidenced by the popularity of the Socialist Party of America (SPA). These turn-of-the-century socialists, still grounded in the democratic republicanism of Marxism and the homegrown democratic republicanism of Tom Paine and the Radical Republicans, were among the most vociferous critics of the Constitution. Victor Berger denounced the Senate (created by Article I, Section 1 of the Constitution) as “an obstructive and useless body, a menace to the liberties of the people, and an obstacle to social growth.” The only solution, Berger declared, was to place all legislative power in the House and strip the Executive and Judicial branches of their veto powers.

Eugene Debs — whose combination of free speech advocacy and constitutional critique, writes Rana, represented the SPA’s “ideological center of gravity” — kept up the heat, exclaiming, “There is not the slightest doubt that the Constitution established the rule of property; that it was imposed upon the people by the minority ruling class of a century and a quarter ago for the express purpose of keeping the propertyless majority in slavish subjection, while at the same time assuring them that under its benign provisions, the people were to be free to govern themselves.” Later, Debs called Gustavus Myers’s History of the Supreme Court, “beyond a doubt the book of the year for Socialists.” Myers, a journalist, historian, and one-time member of the SPA, concluded that “A dominant class must have some supreme institution through which it can express its consecutive demands and enforce its will, whether the insulation be a king, a Parliament, a Congress, a Court or an army. In the United States, the one all-potent institution automatically responding to these demands and enforcing them has been the Supreme Court.”

In 1914, SPA member and soon-to-be presidential candidate Allan Benson wrote Our Dishonest Constitution, a comprehensive dissection of America’s undemocratic political system. The SPA’s newspaper, Appeal to Reason, regularly ran constitutional polemics, such as “Tricked in the Constitution,” published in the March 2, 1912 edition. “Democracy — government by the people or directly responsible to them — was not the object which the Framers had in view,” the article explained. The SPA's national party platforms regularly called for the abolition of the Senate, the direct election of federal judges, and convening a second constitutional convention. Many socialists, including Allan Benson and Crystal Eastman (co-founder of the parent organization of the ACLU), defended civil rights as innate human rights endangered by the Constitution's denial of universal and equal suffrage. Eastman and her collaborators strove to “uproot the existing mode of constitutional decision-making” and ensure “meaningful control by working people over the constitutional system as a whole.” As Benson explained, “‘The rights of citizens would be safeguarded’ only if constitutional power was ‘vested in the people themselves,’ since ‘no flimsy words in a constitution ever safeguarded human rights.’”

Acceptance

However, Rana explains that the demand for a democratic constitution struggled to survive the jingoism and hysteria of war. Exceptions included Chandler Owen and A. Philip Randolph, who used their newspaper, The Messenger (1917-1928), to criticize constitution worship as reactionary, pro-war, and anti-labor. The two men, explains Rana, denounced the “willingness of more moderate Black periodicals to accede to the constitutional celebrations of the times. Those periodicals, wary of being labeled unpatriotic, would repeat bromides about the wisdom of the founders and even support Constitution Day events organized by the likes of the National Security League.”

Still, by the early 1940s, many former critics of the Constitution had changed their tune. “Issues of fundamental reform,” explains Rana, were steadily replaced by “a consolidating faith that the [Constitution] was central to an anti-totalitarian American way of life, which culturally and politically safeguarded citizens from dictatorship.” World War Two dramatically shrank the parameters of political imagination. Americans, the dominant narrative said, had three choices: fascism, communism, or a form of constitutional republicanism that went by the name of democracy. Many previous constitutional skeptics, including Charles Beard and A. Philip Randolph, had a change of heart, and the ACLU and Communist Party “wrapped [themselves] in flag and text.” America had significant problems, the story went, but constitutional critiques were too dangerous during periods of external instability. Many swallowed the idea that checks and balances and the Supreme Court’s use of judicial review were the only things holding back the rise of an indigenous Stalin or Hitler. Notable exceptions included Du Bois (criticized by Owen and Randolph for his pro-war stance in 1916), who dissected the “rotten-borough system” created by the malapportioned Senate in his 1945 work, Color and Democracy.

America’s “constitutional creed” solidified during the Cold War within the general population. The Left remained committed to democracy but had only a tenuous connection to their predecessors’ democratic republican values. Tom Hayden made an ambiguous statement about the Constitution's denial of democracy in the first draft of Students for Democratic Society’s (SDS) Port Huron Statement. A decade earlier, Hayden’s political mentor, C. Wright Mills, described the ubiquity and domination of the “military event.” Americans, Mills explained, “[H]ear that the Congress has again abdicated to a handful of men decisions clearly related to the issue of war or peace. They know that the bomb was dropped over Japan in the name of the United States of America, although they were at no time consulted about the matter. They feel that they live in a time of big decisions; they know that they are not making any.”

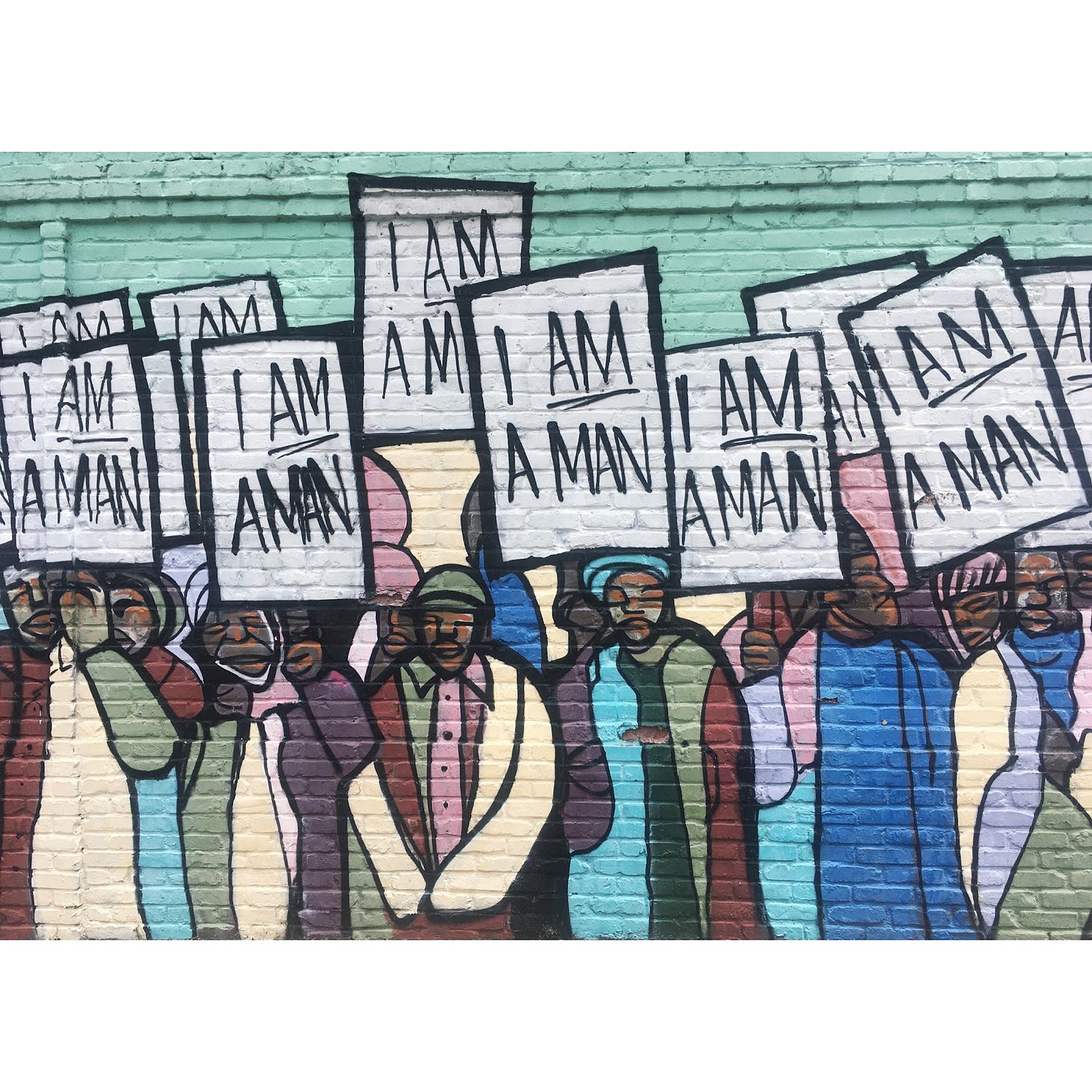

During the Civil Rights Movement, Martin Luther King lamented the limits of the American legal system. In Where Do We Go From Here: Chaos Or Community? (1967), King concluded that his struggle had “left the realm of constitutional rights” and entered “the area of human rights.” To the best of my knowledge, Rana’s is one of the few books (if not the only one) highlighting King’s criticism of the Constitution.

King was murdered before he could expand on his statement. Two years later, the Black Panthers’ People’s Convention marked what Rana calls “the country’s last culturally resonant moment of mass constitutional rejectionism.” However, the convention made the shift from a structural critique to a rights-based critique apparent. While the draft constitution that emerged from the convention took up many new and innovative demands, including ones centered around the family and children's rights, as well as control and use of the military and police, it lacked the pre-Cold War analysis of the bicameral legislature, the Senate, and the Electoral College.

Revival

Some 50 years after the Panthers’ convention, the Left is beginning to discuss the Constitution again. Rana references the political platform of the Democratic Socialists of America (DSA) and its constitutional analysis two times. First, as an exception to the otherwise “limited nature of the current reform conversation.” While most discussions are “largely centered on particular, if valuable, procedural adjustments,” DSA calls for the abolition of the Senate and Electoral College and a second constitutional convention. Second, Rana calls the platform a “conscious effort to update the 1912 SPA legal-political agenda for the present day.”

DSA should consider Rana’s statements a challenge to live up to the SPA’s standards. There is a glaring need for precisely what he describes: a “conscious effort to update the 1912 SPA legal-political agenda for the present day.” So far, DSA has been reluctant to critique the Constitution consistently. This reluctance is seen in the contradictory nature of its 2021 political platform and the recent For Our Rights Committee (FORC) program, which grew out of last year’s Defend Democracy Through Political Independence convention resolution (4).

However, there is hope. Last year, Young Democratic Socialists of America (YDSA) passed “Winning the Battle For Democracy,” which raised the demand for “a new and radically democratic constitution, drafted by an assembly of the people elected by direct, universal and equal suffrage for all adult residents with proportional representation of political parties, and rooted not in the legitimacy of dead generations of slave-owners and capitalists, but that of a majority consensus of the working masses.” YDSA urged all DSA members in and out of elected office to take “concrete actions to advance the struggle for a democratic republic such as agitating against undemocratic Judicial Review, fighting for proportional representation, delegitimizing the anti-democratic U.S. Senate, and advancing the long-term demand for a new democratic Constitution.” Three cheers for the youth.

What We Need

Tom Paine wrote: “When it shall be said in any country in the world, my poor are happy; neither ignorance nor distress is to be found among them; my jails are empty of prisoners, my streets of beggars; the aged are not in want, the taxes are not oppressive; the rational world is my friend, because I am the friend of its happiness: when these things can be said, then may that country boast its constitution and its government.” William Lloyd Garrison burned copies of the Fugitive Slave Law and the Constitution. Thaddeus Stevens and his companions fought tooth and nail to place unimpeded lawmaking power in the legislative branch during the period of Radical Reconstruction. To build the necessary political constituency, socialists can tap into the history of past struggles for democracy in the United States. Rana knows the importance of these struggles. In writing that the Constitution’s flaws from a “‘one person, one vote’ perspective, can be almost too numerous to list,” he is intentionally harkening back to the language of universal and equal rights that dominated the Civil Rights period.

The Constitutional Bind is a comprehensive and accessible account of the Constitution as the central force in American society over the past two-and-a-half centuries. The undemocratic Constitution is a daunting obstacle, but it has a pockmarked history, just like everything else made by human hands. Previous generations of Americans struggled for democracy, and understanding the history of those struggles — the good and the bad — will only benefit those picking up where others left off. Taken individually, all of the constitutional critiques in the world will only amount to firing a peashooter at a battleship. Ultimately, we need a political party that will center the demand for a democratic constitution and stand at the vanguard of the struggle for democracy. We must concentrate all disparate and isolated critiques into one massive force.

The Constitution is a bit like the proverb of the blind men and the elephant: someone touches a leg or the trunk but can’t understand how all the appendages fit together to make a larger whole. Unable to understand what’s going on, the men squabble amongst themselves. Once in a while, someone realizes it’s an elephant but decides to look the other way, maybe thinking the obstacle is too big or that it’s not an opportune time to raise the issue. As Rana’s book demonstrates, socialists in America didn’t always look away.

Many proponents of the Constitution, including Biden, are quick to link the Preamble (along with the Declaration of Independence) to the rest of the text. In fact, the Preamble (let alone the Declaration of Independence) has no legal standing. Some, including Daniel Lazare, have argued that it should.

Notable critiques published as books and articles within the past 40 years include Thomas Geoghegan’s “The Infernal Senate,” Daniel Lazare’s The Frozen Republic and The Velvet Coup, Robert Ovetz’s We the Elites, Jedediah Purdy’s Two Cheers for Politics, Steven Levitsky and Daniel Ziblatt's Tyranny of the Minority, Ari Berman’s Minority Rule, Daniel Lazare’s “A Constitutional Revolution,” and David Dayen’s “America Is Not A Democracy.”

Rana calls his book “a form of social criticism, in which history is presented in service of today’s problems as well as tomorrow’s latent possibilities.”

The political platform calls for the abolition of the Senate and Electoral College. Yet, a few sections later, it calls on the Senate to pass the For the People Act. The FORC program says that its “ultimate goal is working-class majority rule, through a democratic constitution that establishes a political system with universal and equal working-class voting rights, proportional representation in a single federal legislature, and ending the role of money in politics.” Yet, its political demands include nothing more radical than expanding suffrage and eliminating the Senate filibuster. A revival of the SPA’s 1912 program it is not.