Cali-Fragmentation: What’s Madison Got to Do With It?

LA did not turn into a shapeless agglomeration because of too much democracy, but because of too little. By Daniel Lazare

“Divide et impera [divide and conquer], the reprobated axiom of tyranny, is under certain qualifications the only policy by which a republic can be administered on just principles.”

So wrote James Madison to Thomas Jefferson a few weeks after the Constitutional Convention in 1787. What he meant, essentially, is that the only way “we the people” can rule is by dividing ourselves up and then pitting the bits and pieces against one another until self-conquest is achieved. The end product is what the so-called “father of the Constitution” called justice, although, given the parlous state of American politics, self-induced schizophrenia might be more appropriate.

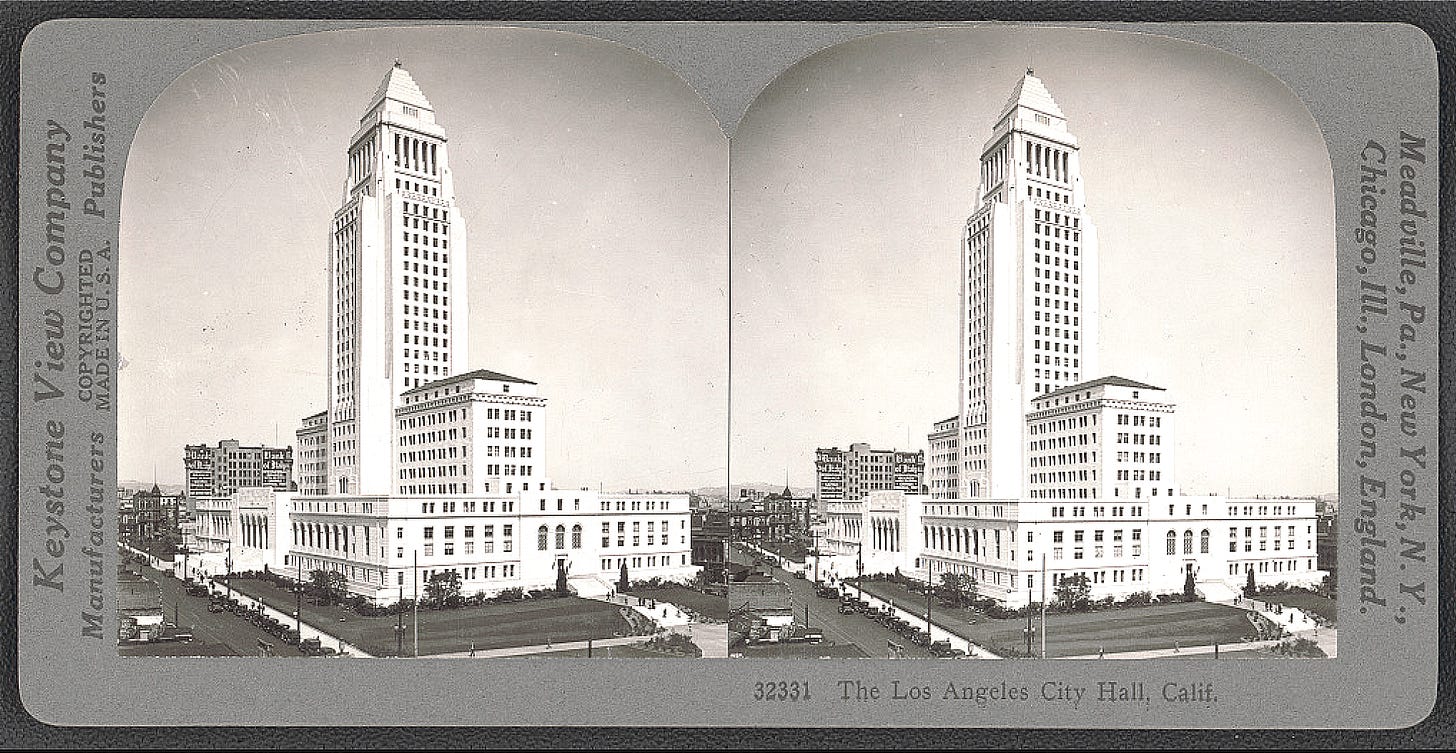

If you want to know what such logic leads to more than two centuries later, then the place to look is scorched-earth Los Angeles.

LA was a case study in Madisonian self-fragmentation even before the latest round of wildfires broke out in early January. Although people speak of Los Angeles as a vague geographical entity, it is in fact a tangle of separate and overlapping jurisdictions. There’s LA County, which contains the city of Los Angeles along with 87 other municipalities. There’s the Los Angeles Unified School District, which covers most but not all of the city plus portions of other municipalities and “unincorporated” county areas nearby. There are 79 other school districts as well. There’s also the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department, the LAPD, and 49 other independent police departments, not to mention 29 fire departments and 142 special districts covering everything from sanitation to lighting, sidewalks, mosquito abatement, and even cemeteries. In addition to the federal and state governments, LA homeowners may thus wind up paying taxes to as many as 20 different local agencies (1).

Ex-governor Gray Davis calls it a “dispersed and discombobulated” system in which lots of people have a hand in one thing or another but no one is in charge overall. Although everyone got very mad at Mayor Karen Bass for being out of the country when the flames erupted — she was in Ghana despite a campaign promise not to indulge in foreign travel — the fact is that she’s merely one of dozens of local politicians whose powers are limited and whose outlook couldn’t be more parochial.

The result is a kind of governmental swarm that leaves local people feeling bewildered and lost. When a retired truck driver named David Long saw his house go up in flames in Pasadena, an “unincorporated” area under direct county supervision, he had no idea what to do: “I don’t know who to go to ask for any help, or even expect to get any.” The same was true of a 99-year-old Pasadenan named Mary McNair, who lost her garage. When asked whom she would turn to for assistance, she replied: “I really don’t know.”

It’s as if there were a separate city government every 10 blocks in Manhattan or a separate school district in Bed-Stuy, Park Slope, and every other Brooklyn neighborhood as well. Rather than justice, the result is a labyrinth in which power is hidden in a dense institutional jungle. The more the average person tries to pick his way through, the more confused he becomes.

But here’s the really bad news: conditions are about to get even worse. According to the New York Times, Los Angeles will soon have five “czars” in charge of post-fire reconstruction. They are:

Steve Soboroff, a long-time civic leader whom Karen Bass has drafted to serve as “chief recovery officer.”

Rick Caruso, a billionaire developer and ex-mayoral candidate putting together a team known as Steadfast LA.

A “public-private philanthropic initiative” known as LA Rises that Gov. Gavin Newsom is assembling.

Another group calling itself the Leadership Council to Rebuild LA that LA Times owner Patrick Soon-Shiong is putting together.

And Richard Grenell, a Republican operative whom Donald Trump says will be his Johnny on the spot.

The result can only be more chaos as various big-shots jostle for attention. Chances of a rebuilding effort that is coordinated, comprehensive, and rational are thus vanishingly small. Meanwhile, Pacific Palisades, a wealthy enclave that lost some 6,800 structures to the blaze, has gotten the bright idea of adding yet another municipality to the mix by breaking away from LA and declaring independence. Rick Caruso says that “social policies” should be tossed by the wayside as Pacific Palisades rebuilds while a local entrepreneur named Jason Finger, founder of a delivery app known as Seamless, says the upshot will be an ever more exclusive community in which low-income housing is banned and cars entering or leaving are followed by drones in case one turns out to be stolen.

“This isn’t just about rebuilding homes; it’s about creating the community of the future, from scratch,” Finger says. “People move here for space, nature, the community, security — not urban density. This should be a model of sustainable, high-end, fireproof residential living, not a policy sandbox.”

All of which illustrates the four iron laws of Madisonian self-conquest. The first is that fragmentation can only lead to more fragmentation since no one is in a position to exert control. The second is that the rich grow richer because the ensuing chaos allows them to use their resources to elbow others aside. The third is that democracy is lost because “we the people” lack any means of imposing reason on a process that is increasingly “disjointed.”

As for the fourth, it couldn’t be clearer: the more dysfunctional the system grows, the more frustrated Angelenos will become — and the greater the likelihood that they will turn to a strong man who will blast the entire structure apart.

Fragmentation leads to economic stratification, which leads to anger, which leads to authoritarianism — in other words, the story of American politics in a nutshell. Barring a financial crisis, overbuilding can only continue. Since 1990, the number of homes in fire-prone areas in California has grown by 40 percent while residential construction in fire-resistant downtown districts grew by just 23. According to one analysis, one California property in eight now faces a “very high” fire risk, a proportion that is certain to rise as the fragmented reconstruction process gives developers and wealthy homeowners a free hand.

How did LA get so bad? Obviously, a lot of factors have gone into the making of a perfect storm that claimed 25 lives, rendered 100,000 homeless, and sent tens of billions of dollars in property up in smoke. Some are natural such as the famous Santa Ana winds that whip small fires up into giant conflagrations as they go roaring through Southern California in late autumn and winter. But some are not such as global warming, which contributes to weather volatility and hence to extended periods of drought, and ill-conceived fire-suppression policies that, by snuffing out small blazes, allow undergrowth to pile up dangerously in “chaparral” shrublands and lead to worse fires in the end.

Then there’s fragmentation and its evil twin suburban sprawl. This is a problem throughout the nation that Madison begat, a land once filled with small towns and mom-and-pop stores but which is now covered with suburbs, highways, gas stations, and drive-thru fast-food joints. But LA sprawl is different due to special local factors. Where cities like Chicago and New York filled up with immigrants from the mid-19th century on, LA was settled decades later by native-born Midwesterners who prized small-town living above all else. According to one historian, such people brought with them

“...a conception of the good community which was embodied in single-family homes, located on large lots, surrounded by landscaped lawns, and isolated from business activities. Not for them multi-family dwellings confined to narrow plots, separated by cluttered streets, and interspersed with commerce and industry. Their vision was epitomized by the residential suburb — spacious, affluent, clean, decent, permanent, predictable, and homogeneous — and violated by the great city — congested, impoverished, filthy, immoral, transient, uncertain, and heterogeneous” (2).

The consequence was an Iowa-by-the-sea filled with people determined to keep big-city vices as far away as possible. When an eastern magazine blamed LA’s ills on transplanted Midwesterners in 1913, locals were irate. “Los Angeles believes in the home,” one reader retorted. “She believes in the moralities; she believes in the decencies of life; she believes that children born within its precincts should be, as far as possible, freed from that familiarity with vice that renders it difficult properly to bring up children in some American cities.” Another was even more florid:

“If anything, it is our departure from the ‘village ideals,’ the simple, comely life of our fathers, that has nurtured the blight of demoralizing metropolitanism, a curse alike to old and young and that embodies in its spirit all those indulgencies and immoralities....”

“Let us have a city without tenements, a city without slums,” proclaimed a prominent local preacher named Dana W. Bartlett. “Ruralize the city; urbanize the country” (3).

Sprawl, decentralization, and the dismantling of one of the best trolley systems in the world all followed, as did highways, traffic, and over-construction in ultra-flammable shrublands. But while local forces played a key role, it was Madisonian self-division that gave them the lead. The whole point of self-division was to make “ambition ... counteract ambition,” as Madison put it in Federalist Paper No. 51, so that no single party or faction could achieve dominance. “A rage for paper money, for an abolition of debts, for an equal division of property, or for any other improper or wicked project” must be prevented, he wrote in Federalist No. 10. And since centralized democracy was the most improper and wicked project of them all from the perspective of the slave-owning Virginia “plantocracy,” it had to be prevented first and foremost.

LA did not turn into a shapeless agglomeration because of too much democracy, but because of too little. It is the complete absence of democratic mechanisms, not only locally but in the nation in general, that makes it impossible to rebuild Los Angeles on a rational basis. Failure will lead to more failure until the entire city collapses. Not only have entire neighborhoods gone up in flames, but an antiquated constitutional structure is self-destructing too.

Robert Kuttner, Revolt of the Haves: Tax Rebellions and Hard Times (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1980), 48-49.

Robert M. Fogelson, The Fragmented Metropolis: Los Angeles, 1850-1930 (Cambridge: Harvard Univ. Press, 1967), 144-45.

Ibid., 190-92.